Introduction

- Dr. Shubhda Chaudhary, Founder, MEI Platform

The Indian Rupee has a storied history as a currency of trade, particularly in the Middle East, where it served as legal tender in several countries during and after British colonial rule.

This analysis explores the use of the Indian Rupee in Middle Eastern countries at the time of India’s independence in 1947, the duration of its usage, the establishment of national currencies in these countries, and the transition away from the Rupee as the primary trading currency.

Additionally, it examines the contemporary adoption of India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) for transactions in Middle Eastern and other countries, alongside potential future adopters, supported by relevant facts and figures.

Part 1: Historical Use of the Indian Rupee in Middle Eastern Countries

Indian Rupee Usage at the Time of Independence (1947)

At the time of India’s independence in 1947, the Indian Rupee was widely used as legal tender in several Middle Eastern countries under British influence, particularly in the Gulf region. These countries included:

- United Arab Emirates (then known as the Trucial States)

- Kuwait

- Bahrain

- Qatar

- Oman

- Aden (Yemen) (used until the 1950s, though primarily under British administration)

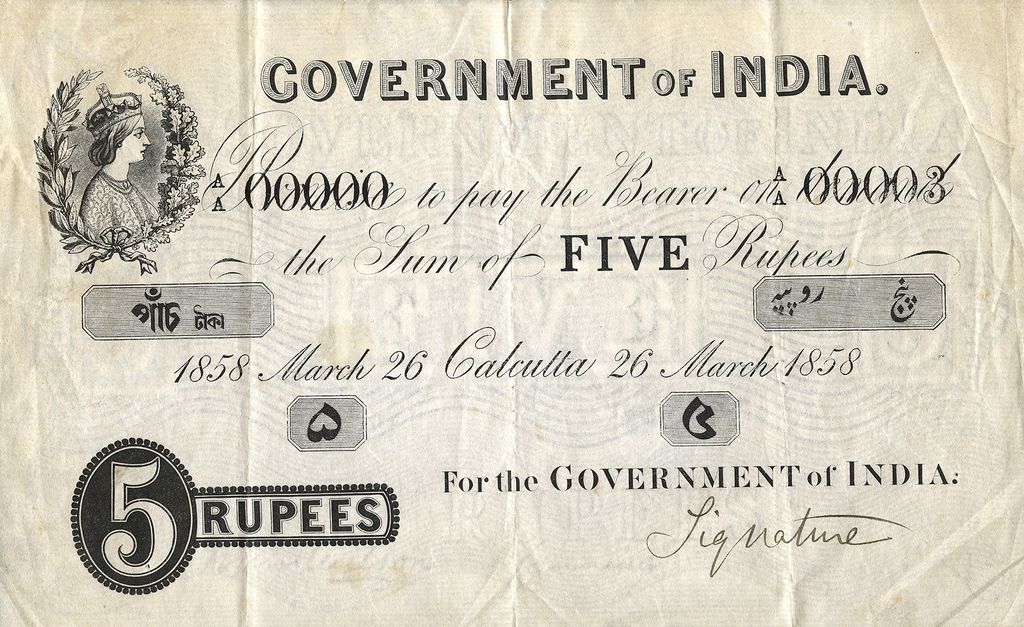

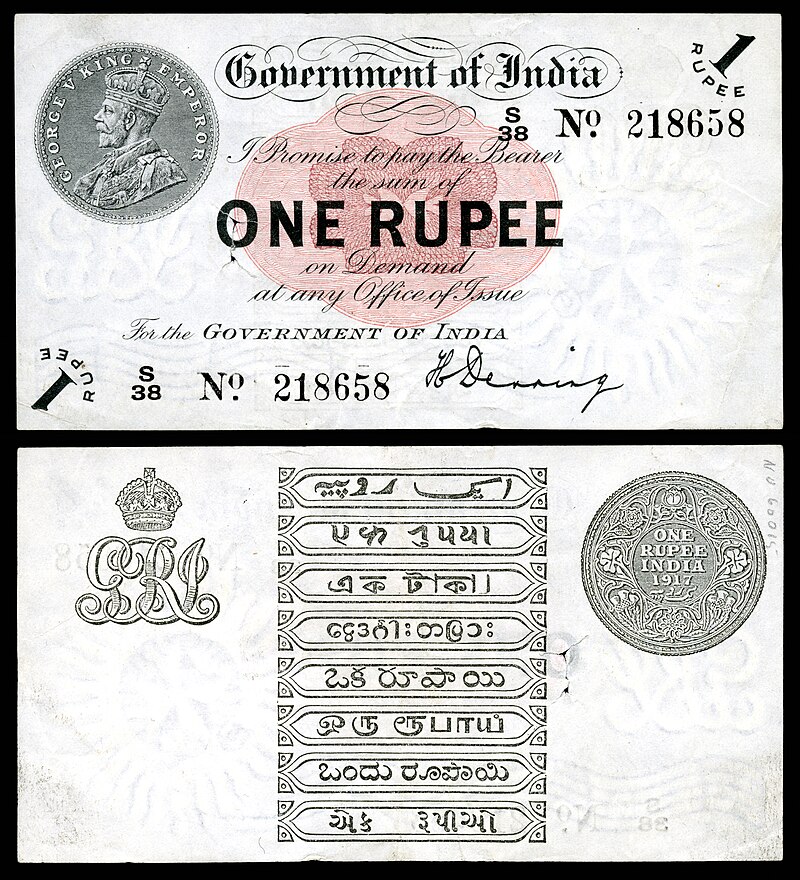

The Indian Rupee’s prominence in these regions stemmed from the British East India Company’s control over India and its trade networks, which extended to the Gulf. The Rupee, a silver-based currency, was a trusted medium of exchange, and its use was reinforced by the British Raj’s governance of these territories as protectorates or colonies.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) managed the currency’s issuance, and Gulf states purchased Rupees from the RBI using sterling reserves.

Duration of Indian Rupee Usage

The Indian Rupee remained in use in these Middle Eastern countries well into the mid-20th century, but its role as legal tender began to wane in the late 1950s due to economic and geopolitical factors, including India’s currency devaluation and the Gulf states’ push for economic sovereignty.

- United Arab Emirates (Trucial States): The Indian Rupee was the official currency until 1959, when India introduced the Gulf Rupee (also known as the Persian Gulf Rupee or external Rupee) to curb gold smuggling. The Gulf Rupee was used exclusively for circulation outside India and remained legal tender until 1966, when India devalued the Rupee significantly. The Trucial States transitioned to the Qatar-Dubai Riyal in 1966, and after the formation of the UAE in 1971, the UAE Dirham was introduced in 1973.

- Kuwait: The Indian Rupee was legal tender until 1959, when the Gulf Rupee was introduced. Kuwait established its own currency, the Kuwaiti Dinar, in 1961, phasing out the Gulf Rupee. The Indian Rupee ceased to be the main trading currency by 1961.

- Bahrain: The Indian Rupee was used until 1959, followed by the Gulf Rupee. Bahrain adopted the Bahraini Dinar in 1965, and the Gulf Rupee was phased out by 1966. The Indian Rupee stopped being the primary trading currency by 1965.

- Qatar: The Indian Rupee was the official currency until 1959, when the Gulf Rupee was introduced. Qatar, along with Dubai, established the Qatar-Dubai Riyal in 1966, which replaced the Gulf Rupee. Qatar introduced the Qatari Riyal in 1973, and the Indian Rupee ceased to be the main trading currency by 1966.

- Oman: The Indian Rupee was used until 1959, followed by the Gulf Rupee. Oman adopted the Saidi Rial in 1970, which was replaced by the Omani Rial in 1972. The Indian Rupee stopped being the primary trading currency by 1970.

- Aden (Yemen): The Indian Rupee was used in Aden under British administration until the early 1950s. After Aden’s integration into Yemen, the South Arabian Dinar was introduced in 1965, and the Indian Rupee was no longer used for trading by the mid-1950s.

Establishment of National Currencies

The transition to national currencies in these Middle Eastern countries was driven by several factors:

- Devaluation of the Indian Rupee: The significant devaluation of the Indian Rupee in 1966 (by approximately 57%) eroded confidence in the currency, prompting Gulf states to establish their own currencies to ensure economic stability.

- Gold Smuggling Concerns: The smuggling of gold from India to the Gulf in exchange for Rupees led to the creation of the Gulf Rupee in 1959, but this was a temporary measure.

- Political Independence: As Gulf states gained independence from British protection (e.g., Kuwait in 1961, UAE in 1971), they sought to assert economic sovereignty by issuing their own currencies.

- Economic Growth: The discovery of oil reserves in the Gulf increased economic activity, necessitating robust, independent monetary systems.

Timeline of National Currency Establishment:

- Kuwait: Kuwaiti Dinar (1961)

- Bahrain: Bahraini Dinar (1965)

- Qatar: Qatar-Dubai Riyal (1966), Qatari Riyal (1973)

- Oman: Saidi Rial (1970), Omani Rial (1972)

- UAE: Qatar-Dubai Riyal (1966), UAE Dirham (1973)

- Aden (Yemen): South Arabian Dinar (1965)

Cessation of the Indian Rupee as the Main Trading Currency

The Indian Rupee (and its variant, the Gulf Rupee) ceased to be the primary trading currency in these countries as follows:

- Kuwait: 1961 (Kuwaiti Dinar introduction)

- Bahrain: 1965 (Bahraini Dinar introduction)

- Qatar: 1966 (Qatar-Dubai Riyal introduction)

- UAE: 1966 (Qatar-Dubai Riyal), fully phased out by 1973 (UAE Dirham)

- Oman: 1970 (Saidi Rial introduction)

- Aden (Yemen): Mid-1950s (shift to British-controlled currencies, later South Arabian Dinar)

By the early 1970s, the Indian Rupee had been entirely replaced as the main trading currency in the Middle East, marking the end of its historical dominance in the region.

Part 2: Adoption of India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI)

Current Adoption of UPI in Middle Eastern and Other Countries

India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI), launched in 2016 by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), has revolutionized digital payments domestically and is now gaining traction internationally.

UPI enables seamless, real-time, and low-cost transactions via mobile devices, making it an attractive payment system for cross-border adoption. As of January 2024, UPI has been adopted or is in the process of being integrated in several countries, including some in the Middle East.

Middle Eastern Countries Adopting UPI:

- United Arab Emirates:

- Adoption Status: UPI has been integrated for use by Indian tourists and residents in the UAE through partnerships with local payment providers. In 2019, NPCI International Payments Limited (NIPL) partnered with Mashreq Bank to enable UPI transactions at retail outlets and ATMs in the UAE. Indian visitors can use UPI apps like BHIM, Google Pay, or PhonePe to make payments at merchants displaying QR codes compatible with UPI.

- Transaction Volume: In 2023, UPI transactions in the UAE accounted for approximately 10% of cross-border UPI transactions by Indian users abroad, with an estimated value of ₹5,000 crore (US$600 million). The UAE is a significant destination due to its large Indian diaspora (over 3.5 million) and tourism flows (1.2 million Indian visitors annually).

- Impact: UPI reduces transaction costs for Indian expatriates sending remittances and for tourists, eliminating the need for currency conversion or high card fees.

- Oman:

- Adoption Status: Oman has implemented UPI for Indian tourists and the Indian diaspora (approximately 700,000 residents) through collaborations with local banks like BankDhofar. Launched in 2022, UPI acceptance is available at select retail and hospitality outlets.

- Transaction Volume: Cross-border UPI transactions in Oman are smaller, with an estimated ₹500 crore (US$60 million) in 2023, but growing steadily due to increasing merchant adoption.

- Impact: UPI strengthens economic ties by facilitating seamless payments for Indian workers and visitors, reducing reliance on cash or international cards.

Other Countries Adopting UPI: Beyond the Middle East, UPI has been adopted in:

- Singapore: Through a partnership between NPCI and PayNow (Singapore’s real-time payment system), UPI-PayNow linkage was launched in February 2023, enabling instant cross-border transfers. In 2023, the linkage processed over 1 million transactions valued at ₹2,000 crore (US$240 million).

- Malaysia: UPI integration began in 2024 with Payments Network Malaysia (PayNet), allowing Indian tourists to use UPI at merchants. Transaction volumes are nascent, estimated at ₹100 crore (US$12 million) in 2024.

- Bhutan: UPI is widely used due to the Bhutanese Ngultrum’s peg to the Indian Rupee. Launched in 2021, UPI accounts for 30% of digital transactions in Bhutan, with a value of ₹1,500 crore (US$180 million) in 2023.

- Nepal: UPI was introduced in 2022 through Fonepay, Nepal’s payment network. It is used by Indian tourists and for cross-border remittances, with transactions worth ₹1,000 crore (US$120 million) in 2023.

- France: In 2024, UPI was launched in France, starting with the Eiffel Tower and expanding to retail. It primarily serves Indian tourists, with transactions of ₹200 crore (US$24 million) in 2024.

- Sri Lanka: UPI was rolled out in 2024 for tourism and trade, with transactions of ₹300 crore (US$36 million) in 2024.

- Mauritius: Similar to Sri Lanka, UPI was introduced in 2024, with transactions of ₹200 crore (US$24 million) in 2024.

Total Cross-Border UPI Transactions: In 2023, UPI processed over 74.05 billion domestic transactions worth ₹126 trillion (US$1.5 trillion). Cross-border transactions, while smaller, reached 100 million transactions valued at ₹50,000 crore (US$6 billion) in 2023, with the Middle East (primarily UAE and Oman) contributing 15% of this volume.

Potential Future Adopters of UPI

Several countries, particularly in the Middle East and Asia, are potential candidates for adopting UPI due to economic ties with India, large Indian diasporas, or interest in reducing reliance on US dollar-based payment systems. Factors driving potential adoption include:

- Trade Relations: Countries with significant trade with India (e.g., Saudi Arabia, UAE) benefit from lower transaction costs via UPI.

- Diaspora and Tourism: Nations with large Indian populations or tourist inflows (e.g., Qatar, Bahrain) are likely to adopt UPI for remittances and payments.

- Geopolitical Alignment: BRICS nations and those seeking alternatives to SWIFT or dollar-based systems (e.g., Russia, Iran) may explore UPI integration.

- Digital Infrastructure: Countries with advanced payment systems can integrate UPI more easily (e.g., Singapore, Malaysia).

Middle Eastern Countries as Potential Adopters:

- Saudi Arabia:

- Rationale: Saudi Arabia is India’s fourth-largest trading partner, with bilateral trade of US$52 billion in 2022-23. The Indian diaspora in Saudi Arabia numbers 2.6 million, and remittances to India exceed US$10 billion annually. Discussions for a Rupee-Riyal trade mechanism are ongoing, and UPI could complement this by enabling direct payments.

- Feasibility: Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 emphasizes digital payments, and its payment system (SARIE) could integrate with UPI. Pilot programs for UPI acceptance at retail outlets catering to Indian tourists are under consideration.

- Potential Impact: UPI adoption could save 20-30% in remittance costs for Indian workers, boosting annual savings by US$2-3 billion.

- Qatar:

- Rationale: Qatar hosts 750,000 Indian residents, and bilateral trade reached US$18 billion in 2022-23. The Indian Rupee’s historical use in Qatar until 1966 creates a cultural precedent for Rupee-based transactions.

- Feasibility: Qatar’s digital payment infrastructure, led by Qatar Central Bank, is compatible with UPI integration. Talks for UPI adoption began in 2024, focusing on tourism and remittances.

- Potential Impact: UPI could process US$1 billion in transactions annually, reducing costs for Indian expatriates.

- Bahrain:

- Rationale: Bahrain has a 350,000-strong Indian community and bilateral trade of US$2 billion. Its open financial system makes it a candidate for UPI adoption.

- Feasibility: Bahrain’s BenefitPay could integrate with UPI, similar to Singapore’s PayNow. Exploratory discussions started in 2024.

- Potential Impact: UPI could handle US$500 million in transactions, enhancing financial inclusion for Indian workers.

- Kuwait:

- Rationale: Kuwait has 1 million Indian residents and US$12 billion in bilateral trade. Remittances to India are significant, at US$4 billion annually.

- Feasibility: Kuwait’s KNET payment system could support UPI integration, with potential pilots in 2025.

- Potential Impact: UPI adoption could save US$800 million in transaction costs annually.

Other Potential Adopters:

- Russia: Amid sanctions and a shift away from SWIFT, Russia has explored Rupee-based trade and UPI integration. In 2023, Russia settled US$2 billion in trade with India using Rupees, and UPI could streamline retail transactions for Indian businesses.

- Bangladesh: With US$18 billion in trade and proximity to India, Bangladesh is a strong candidate. UPI trials are planned for 2025, leveraging Bangladesh’s bKash payment system.

- Thailand: As a tourism hub for Indians (1.5 million visitors annually), Thailand could adopt UPI for retail payments, with discussions underway since 2024.

- South Africa: As a BRICS member, South Africa is exploring UPI to reduce dollar dependency, with potential pilots in 2025.

Challenges to UPI Adoption:

- Regulatory Hurdles: Countries must align data privacy and financial regulations with India’s, which can delay integration.

- Infrastructure Costs: Smaller economies may lack the digital infrastructure to support UPI, requiring investments.

- Merchant Adoption: Convincing local merchants to accept UPI requires awareness and incentives.

- Competition: Global payment systems like SWIFT, Visa, or China’s CIPS may compete with UPI.

Part 3: Broader Implications and Analysis

Historical Context and Modern Parallels

The Indian Rupee’s historical use in the Middle East reflects India’s economic influence under British rule, facilitated by trade routes and colonial administration.

Its decline was tied to India’s economic challenges (e.g., 1966 devaluation) and the Gulf’s oil-driven prosperity, which demanded independent currencies.

Today, UPI’s adoption mirrors a resurgence of India’s financial influence, driven by its digital innovation and the global push for de-dollarization.

The Rupee’s internationalization, supported by UPI, aims to reduce transaction costs and enhance India’s geopolitical clout, much like its historical role in the Gulf.

Economic Impact of UPI Adoption

- Cost Reduction: UPI’s low-cost model (near-zero transaction fees domestically) can save 20-50% on cross-border transaction costs compared to SWIFT or card networks. For instance, Sri Lankan businesses save 50% by using Rupee-based UPI transactions instead of dollar-based systems.

- Trade Facilitation: UPI enables Rupee invoicing, reducing currency risk for Indian exporters. In 2023, 18 countries, including the UAE, opened Special Vostro Rupee Accounts (SVRAs) for Rupee trade, processing US$10 billion in transactions.

- Remittance Efficiency: UPI can lower remittance costs for the Indian diaspora (e.g., US$100 billion annually from the Gulf), boosting disposable income and India’s forex reserves.

- Financial Inclusion: UPI’s accessibility via mobile phones promotes financial inclusion in countries with unbanked populations, such as Nepal and Bhutan.

Geopolitical Significance

UPI’s expansion aligns with India’s strategic goals:

- De-Dollarization: By promoting Rupee-based transactions, UPI supports BRICS efforts to reduce reliance on the US dollar, especially post-Ukraine sanctions on Russia.

- Regional Influence: Adoption in South Asia (Bhutan, Nepal) and the Middle East strengthens India’s economic leadership in these regions.

- Global Fintech Leadership: India’s UPI, handling 74.05 billion transactions in 2023, positions it as a fintech innovator, rivaling China’s WeChat Pay and Alipay.

Future Outlook

The internationalization of the Rupee, supported by UPI, is a long-term project. The RBI aims for full Rupee convertibility by 2060, which would enhance UPI’s global adoption. Key milestones include:

- Expanding SVRAs: Increasing the number of countries using Rupee trade accounts, potentially reaching 50 by 2030.

- CBDC Integration: The Digital Rupee (e₹), launched in 2022, could integrate with UPI for cross-border CBDC transactions, enhancing security and speed.

- Policy Reforms: Liberalizing capital account transactions and deepening India’s financial markets will boost UPI’s appeal.

Conclusion

The Indian Rupee’s historical role as legal tender in Middle Eastern countries like the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and Aden underscores India’s past economic influence, which waned by the 1970s due to devaluation and Gulf independence.

Today, UPI’s adoption in the UAE and Oman, with potential expansion to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait, signals a revival of India’s financial outreach.

Supported by robust digital infrastructure and geopolitical alignments, UPI processed US$6 billion in cross-border transactions in 2023, with the Middle East playing a pivotal role.

Future adopters, driven by trade, diaspora, and de-dollarization trends, could elevate UPI’s global footprint, positioning India as a leader in digital finance.

Leave a comment