Pakistani Defense Minister Khawaja Asif has stated that “Escalation between New Delhi and Islamabad is currently possible.”

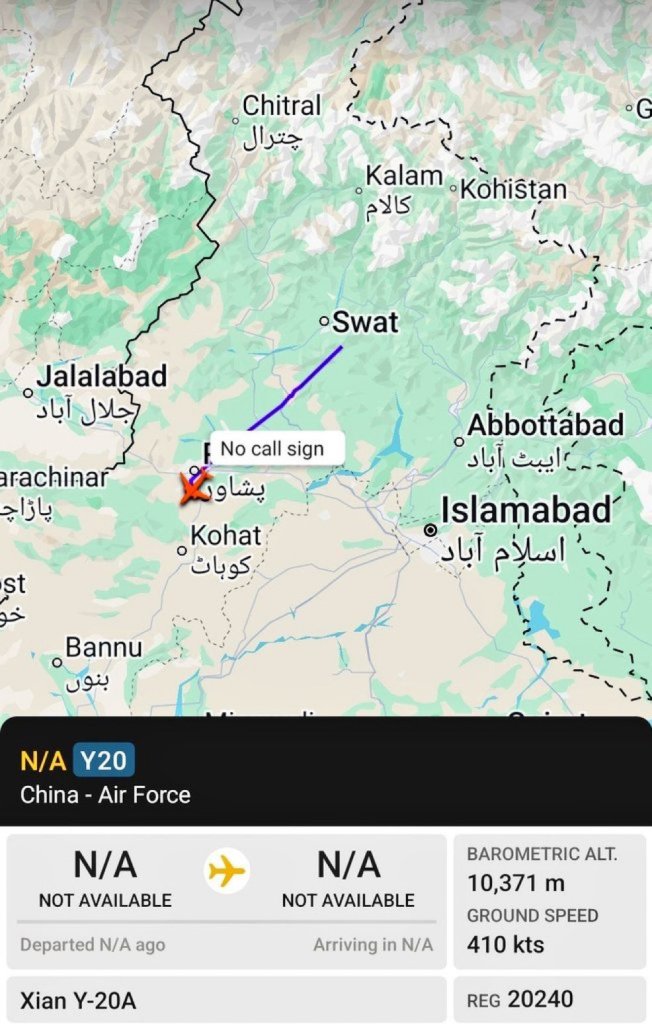

Meanwhile, Chinese PLAAF Y-20 cargo aircraft departed Saidu Shariff Airport in Swat, Pakistan and is currently en route to an unknown destination.

The Chinese PLAAF Y-20 cargo aircraft, spotted departing Saidu Sharif Airport in Swat, Pakistan, on April 28, 2025, is a strategic asset capable of carrying up to 66 tons of cargo, often used for military logistics like delivering air defense systems such as the HQ-9B, which can cover a 300 km radius and potentially block aerial access over Indian-administered Kashmir.

India has banned 16 Pakistani YouTube channels for “spreading misinformation” after the deadly Pahalgam attack that killed 26. The ban targets major outlets like Dawn News, ARY News, Geo News, and journalists like Irshad Bhatti and Asma Shirazi. Former cricketers Shoaib Akhtar and Basit Ali’s YouTube channels were also blocked in India.

Pakistan’s Army carried out another timely operation, resulting in the killing of 17 terrorists of the TTP who were attempting to infiltrate Pakistan from Afghanistan. In the last 48 hours, 71 terrorists have been killed.

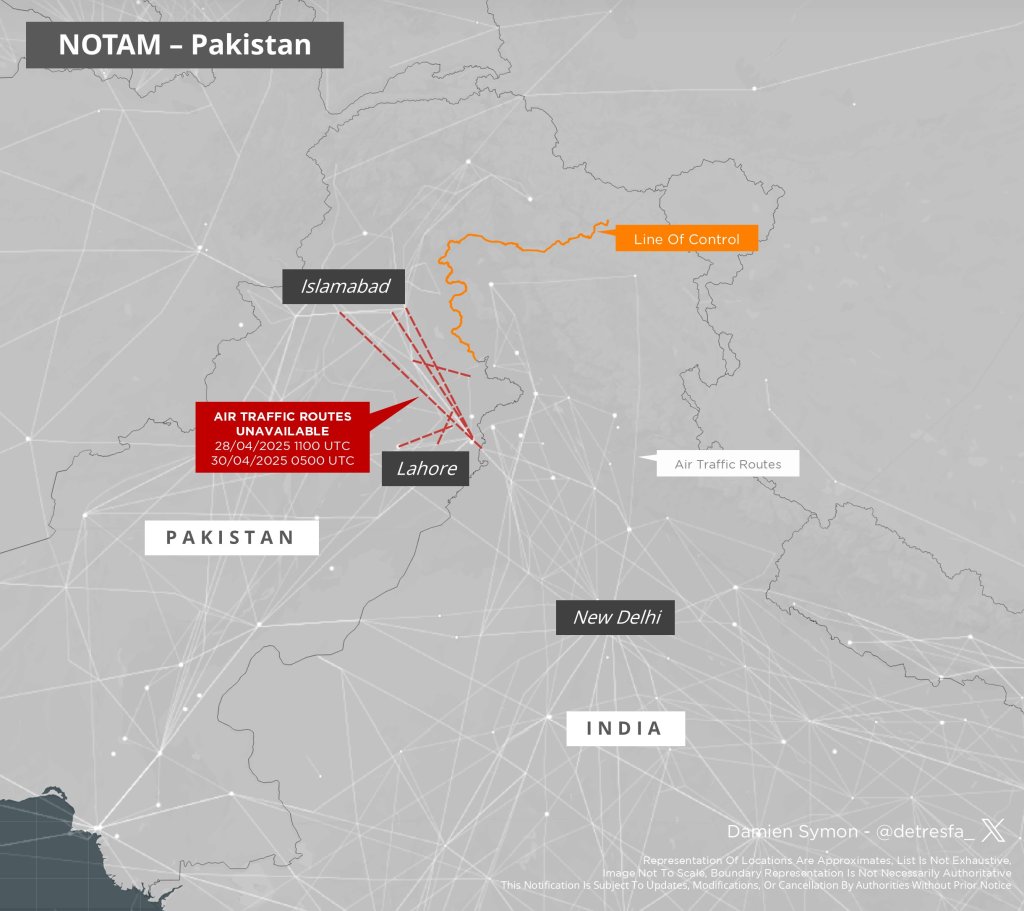

The Pakistan Air Force launched “Fiza-e-Badr” and “Lalkar-e-Momin” exercises on April 28, 2025, involving its Northern and Central Commands, with most combat fleets, drones, air defenses, and electronic warfare (EW) assets deployed, signaling a significant military readiness test amid regional tensions.

Alleged Resignations in Pakistan Army Post-Pahalgam Attack

The April 22, 2025, terror attack in Pahalgam, Kashmir, which killed 26 people, has escalated India-Pakistan tensions to a critical juncture. Amid this, unverified reports of mass resignations within the Pakistan Army—ranging from 250 to 4,500 personnel—have surfaced, primarily through social media platforms like X. These claims, allegedly linked to internal morale crises and fears of Indian retaliation, lack official confirmation and raise questions about their authenticity.

The resignation narrative primarily stems from posts on X, amplified by viral accounts with limited vetting. Key claims include:

- Scale of Resignations: One post alleges over 250 officers and 1,200 soldiers resigned, citing an internal letter from Lt. Gen. Omer Ahmed Bokhari to General Munir. Another claims 2,500–4,500 resignations, acknowledging the possibility of fabricated documents.

- Internal Advisory: A web report references a classified advisory by Major General Faisal Mehmood Malik, addressing morale collapse and resignation requests, framed as a response to fears of Indian military retaliation.

- Motivations: Alleged reasons include low morale, distrust in leadership, and apprehension about India’s potential escalation, particularly following Prime Minister Modi’s public vow of a “befitting reply.”

These claims, however, lack corroboration from official Pakistani sources, mainstream media, or credible intelligence leaks. The reliance on unverified documents and anonymous X posts raises red flags about their authenticity.

Countries Supplying Arms to India and Pakistan

Several global powers supply arms to both India and Pakistan, driven by economic interests, strategic alignments, and geopolitical balancing.

The primary suppliers—United States, Russia, China, France, and Israel—are discussed below, with timelines and quantities based on SIPRI data and recent reports.

United States

- Timeline:

- Pakistan: Arms supplies began in the 1950s under Cold War alliances (SEATO, CENTO). F-16 jet sales started in 1982, paused in 1990 due to nuclear-related sanctions, and resumed post-2001 after 9/11 lifted sanctions.

- India: Significant arms sales commenced in the early 2000s, with major deals post-2005 under the U.S.-India strategic partnership, focusing on maritime and air assets.

- Quantities:

- Pakistan: 40 F-16A/B jets (1980s); 36 F-16C/D Block 50/52 jets, 500 AMRAAM missiles, 200 Sidewinder missiles, and 3,100 laser-guided bombs (2006, ~$5.1 billion).

- India: 24 MH-60 Romeo helicopters ($2 billion, 2020, deliveries by 2025) with Hellfire missiles and Mk 54 torpedoes; 12 P-8I Poseidon aircraft, 6 C-130J Super Hercules, Apache/Boeing helicopters (~$10 billion since 2010); $300 million in MH-60 armaments (2023).

- Strategic Implications: The U.S. balances relations with both nations, using arms sales to secure counterterrorism cooperation from Pakistan and counter-China alignment from India. Economic gains are significant, with billions in revenue.

Russia

- Timeline:

- India: Russia (and formerly the USSR) has been India’s primary supplier since the 1960s, providing MiG fighters, T-90 tanks, and S-400 systems.

- Pakistan: Limited arms sales began in 2014 with Mi-35 helicopters, with discussions for Su-35 jets and T-90 tanks post-2016, though no major jet deals materialized.

- Quantities:

- India: Over 700 MiG-21/23/27, Mirage 2000, and Jaguar aircraft since the 1970s (~300 active); 272 Su-30MKI fighters ($12 billion since 1996); 5 S-400 squadrons ($5.4 billion, deliveries from 2021); missiles like R-77, R-73, and potential R-37M.

- Pakistan: 4 Mi-35M helicopters (2017, ~$150 million).

- Strategic Implications: Russia maintains India as a key market (62% of India’s arms imports, 2019–2023) while cautiously engaging Pakistan to diversify markets post-Ukraine sanctions. Delays in S-400 deliveries to India highlight supply chain vulnerabilities.

China

- Timeline:

- Pakistan: China has been Pakistan’s primary supplier since the 1960s, with significant growth post-2000 via JF-17 jets, submarines, and missiles.

- India: No direct arms sales due to strategic rivalry, though China’s S-400 operations raise concerns about shared intelligence with Pakistan.

- Quantities:

- Pakistan: Over 130 JF-17 Thunder jets (2003–present, ~$32 million per Block III); 8 Hangor-class submarines ($4–5 billion, 2015, 4 delivered by 2025); PL-15 missiles (2025 emergency delivery); HQ-9 systems; 25 J-10CE jets (~$1.5 billion); drones.

- India: None directly.

- Strategic Implications: China, supplying 81% of Pakistan’s arms (2020–2024), uses Pakistan to counter India, securing influence in the Indian Ocean and Gwadar port. The PL-15 enhances Pakistan’s air capabilities, though India’s diversified arsenal mitigates this threat.

France

- Timeline:

- India: Arms supplies began in the 1980s with Mirage 2000 jets, with major Rafale deals post-2016.

- Pakistan: Mirage III/V jets supplied in the 1960s–1970s; Agosta-90B submarines in the 1990s. Sales dwindled post-2000 due to India’s market dominance.

- Quantities:

- India: 36 Rafale jets ($7.4 billion, 2016, deliveries completed 2022); 50 Mirage 2000 jets (1980s, ~40 active, upgraded with Mica missiles); 6 Scorpene-class submarines ($3.7 billion, deliveries ongoing).

- Pakistan: ~100 Mirage III/V jets (1960s–1970s, ~70 active, upgraded); 3 Agosta-90B submarines (1990s, ~$1 billion).

- Strategic Implications: France prioritizes India for economic and strategic reasons, with Rafale jets enhancing India’s air superiority. Pakistan’s aging Mirage fleet limits its competitive edge.

Israel

- Timeline:

- India: Arms sales grew post-1990s, with significant deals for drones, missiles, and radar systems since 2000.

- Pakistan: No direct sales, but Israeli components in U.S. and European platforms (e.g., F-16 avionics) indirectly reach Pakistan.

- Quantities:

- India: SPICE 2000 smart bombs, Barak-8 missiles, Heron drones, and AWACS systems (~$5 billion since 2000).

- Pakistan: Indirect access via U.S. F-16 avionics and European systems.

- Strategic Implications: Israel’s focus on India strengthens its position as a reliable supplier, with SPICE bombs enhancing precision strikes. Indirect transfers to Pakistan are minimal but raise concerns about technology leakage.

Hypothetical War Benefits

In a hypothetical India-Pakistan war, the arms supplied by these countries would shape the conflict’s dynamics, with outcomes hinging on air superiority, naval capabilities, and missile effectiveness.

- Pakistan:

- U.S. F-16s and AMRAAM Missiles: Enable beyond-visual-range (BVR) engagements and nuclear-capable strikes, targeting Indian air bases or AWACS. Limited numbers (76 F-16s) constrain sustained operations.

- Chinese JF-17s and PL-15 Missiles: Enhance BVR combat, threatening high-value Indian assets like tankers. Hangor-class submarines provide stealthy naval strikes, though outnumbered by India’s fleet.

- Russian Mi-35 Helicopters: Support ground attacks but lack strategic impact due to small quantities.

- French Mirage Jets: Aging but capable for ground attack; Agosta-90B submarines offer limited naval disruption.

- Constraints: Pakistan’s smaller air force (~400 combat aircraft vs. India’s ~800) and reliance on Chinese systems, less advanced than India’s diversified arsenal, limit escalation potential.

- India:

- U.S. P-8I and MH-60 Helicopters: Bolster maritime surveillance and anti-submarine warfare, securing sea lanes against Pakistani submarines. Hellfire missiles enhance naval strike precision.

- Russian Su-30MKIs and S-400 Systems: Provide air superiority and robust air defense, countering Pakistani F-16s and JF-17s. S-400’s 400 km range deters air incursions.

- French Rafale Jets and Meteor Missiles: Outmatch Pakistan’s air capabilities with advanced radar and 150+ km BVR missiles. Scorpene submarines counter Pakistan’s naval assets.

- Israeli SPICE Bombs and Drones: Enable precision strikes on Pakistani infrastructure and real-time battlefield intelligence.

- Advantages: India’s larger, modernized arsenal, superior radar, and electronic warfare systems provide a qualitative and quantitative edge, particularly in sustained operations.

- Supplier Benefits: Arms suppliers profit economically (e.g., U.S. $15 billion, Russia $17 billion, China $6 billion from 2010–2023) and gain strategic leverage. A war would spike demand for munitions and replacements, further enriching suppliers. China strengthens Pakistan to counter India, while the U.S. and Russia balance both to maintain regional influence.

Economic Costs of Past India-Pakistan Wars

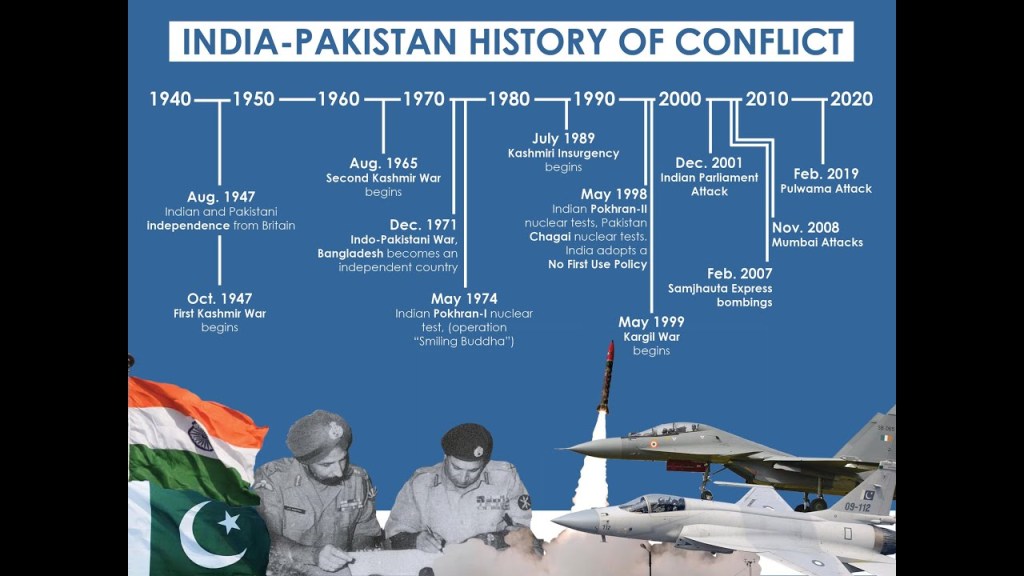

India and Pakistan have fought four major wars (1947–48, 1965, 1971, 1999) and numerous skirmishes, with significant economic costs:

- 1947–48 War: Limited data exists, but costs included military mobilization and refugee resettlement. India’s GDP growth stagnated at ~2%, while Pakistan’s nascent economy faced severe strain.

- 1965 War: India spent ~$800 million (1965 USD, ~2.5% of GDP); Pakistan ~$500 million (~3% of GDP). Both economies slowed, with India’s GDP growth dropping to 2.6% and Pakistan’s to 3.1%.

- 1971 War: India’s costs were ~$1.5 billion (~3.5% of GDP), including Bangladesh liberation support; Pakistan’s ~$1 billion (~4% of GDP). Pakistan’s economy contracted by 1.2% in 1972, exacerbated by East Pakistan’s loss. India’s growth slowed to 1.7%.

- 1999 Kargil War: India’s costs ~$2 billion (~0.4% of GDP); Pakistan’s ~$1 billion (~1.5% of GDP). Pakistan’s economy grew at 3.1% but faced sanctions; India’s growth was 8.2% but diverted resources from development.

- Skirmishes (e.g., 2019): The 2019 Balakot airstrike cost India ~$100 million (jets, munitions); Pakistan’s response ~$50 million. Economic disruptions included trade suspensions and airspace closures.

- Total Costs: Adjusted for inflation, cumulative costs exceed $20 billion (2025 USD), with indirect losses (trade, investment, infrastructure) doubling this figure. Both nations diverted funds from education, healthcare, and infrastructure, perpetuating developmental challenges.

Policy Recommendations for the Indian Government

Given the strategic and economic implications, India must adopt a multifaceted approach to reduce vulnerabilities and enhance deterrence:

- Diversify Arms Suppliers: While Russia remains critical (62% of imports), delays in S-400 deliveries highlight risks. India should deepen ties with the U.S. (MH-60, P-8I), France (Rafale, Scorpene), and Israel (drones, missiles) to mitigate supply chain disruptions. Engaging emerging suppliers like Bulgaria or Poland for Soviet-era spares is viable.

- Accelerate Indigenous Production: The ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ initiative must prioritize cost-effective platforms like Tejas fighters and Astra missiles. Private sector participation (e.g., Adani, Tata) and DRDO efficiency are critical to reduce import reliance (11% of global arms imports).

- Counter Chinese Influence: China’s PL-15 and J-10CE supplies to Pakistan escalate threats. India should invest in Astra Mk-2 and R-37M missiles to maintain BVR superiority and lobby Russia to limit technology transfers to China that could reach Pakistan.

- Strengthen Deterrence: Deploy S-400 systems along the Line of Control and enhance Rafale squadrons to deter Pakistani air incursions. Maritime assets (P-8I, Scorpene) should secure the Arabian Sea against Chinese-Pakistani naval cooperation.

- Diplomatic Engagement: Engage the U.S. to limit F-16 upgrades to Pakistan, emphasizing India’s role in countering China. Backchannel diplomacy with Pakistan, mediated by neutral parties (e.g., UAE), could reduce escalation risks.

- Economic Resilience: Allocate defense budgets efficiently (Rs 6.81 trillion in 2025, ~1.9% of GDP) to balance modernization with development. Past wars show high opportunity costs; India must avoid protracted conflicts to sustain 7–8% GDP growth.

Conclusion

The arms race between India and Pakistan, fueled by suppliers like the U.S., Russia, China, France, and Israel, reveal the complex interplay of economic and strategic interests in South Asia.

In a hypothetical war, India’s diversified and modernized arsenal provides a decisive edge, but escalation risks nuclear consequences.

Past wars highlight significant economic costs, diverting resources from development. India must diversify suppliers, boost indigenous production, counter Chinese influence, strengthen deterrence, and pursue diplomacy to navigate this volatile landscape.

By balancing military modernization with economic resilience, India can secure its strategic interests while minimizing conflict risks.

Leave a comment