By Dr. Shubhda Chaudhary, MEI Analysis

17 May 2025

The India-Pakistan rivalry, rooted in historical disputes over Kashmir and marked by nuclear capabilities, has long been a flashpoint in South Asia. Recent escalations, notably following the April 2025 terrorist attack in Pahalgam, have intensified military tensions, raising questions about whether this conflict is evolving into a proxy warfare arena for global powers like the United States, France, Russia, China, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Israel.

These nations, with their advanced arms industries, are increasingly supplying sophisticated weaponry to both sides, prompting speculation that the region serves as a testing ground for weapons systems and a marketplace for defence exports.

This analysis, grounded in international relations theory, critically examines this claim, highlighting the motivations of external powers, the dynamics of proxy conflict, and the risks of escalation, while questioning the assumptions underpinning the “testing ground” narrative.

The Context: A Volatile Rivalry

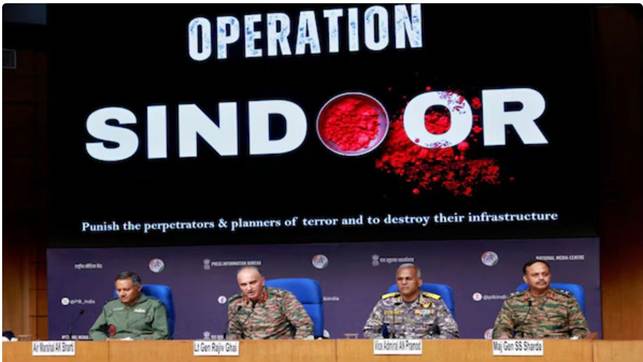

The India-Pakistan conflict, reignited by the Pahalgam attack that killed 26 tourists, has seen both nations deploy advanced weaponry, including drones, missiles, and fighter jets. India’s Operation Sindoor targeted sites in Pakistan, while Pakistan retaliated with strikes on Indian cities like Amritsar and Jammu.

This escalation, the most significant since 2019, involved French Rafale jets, Chinese J-10 fighters, Israeli Harop drones, and Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones, signify the role of external arms suppliers. The Line of Control (LoC) remains a hotspot, with both sides accusing each other of violating ceasefire agreements.

From a realist perspective in international relations, states prioritize power and security.

For India and Pakistan, acquiring advanced weaponry enhances deterrence and national security in a nuclearized rivalry. However, the involvement of multiple global powers suggests a broader geopolitical game, potentially aligning with neorealist views that emphasize systemic pressures and alliances in shaping state behavior. Yet, the assumption that these powers are deliberately using South Asia as a proxy war testing ground requires scrutiny.

India, the world’s largest arms importer with a 9.8% share of global arms imports in 2019–23, has strategically diversified its defense procurement to bolster its military capabilities amid tensions with China and Pakistan. Historically reliant on Russia, India has increasingly turned to the United States, France, and Israel for advanced technologies, while fostering its indigenous defense industry, exemplified by systems like the BrahMos missile. Drawing on liberal institutionalist theories, we explore how economic interdependence and strategic cooperation shape these relationships, supported by facts, figures, and recent developments.

India’s Arms Suppliers: A Shifting Landscape

United States: Countering China in the Indo-Pacific

The United States has emerged as a pivotal arms supplier to India, driven by a shared interest in countering China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific. Bilateral defense trade, which was near zero in 2008, reached $15 billion by 2019, reflecting deepening ties. Key U.S. supplies include Predator drones, Apache and Chinook helicopters, and long-range maritime patrol aircraft like the P-8 Poseidon. These systems enhance India’s surveillance and strike capabilities, particularly in contested regions like the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China.

The U.S. motivation aligns with liberal institutionalist theories, where strategic cooperation fosters mutual security benefits. By arming India, the U.S. strengthens a key partner in the Quad (comprising the U.S., India, Japan, and Australia), countering China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea and beyond.

For instance, the 2018 Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) enabled the transfer of encrypted communication systems, facilitating interoperability. However, U.S. arms sales also serve economic interests, with companies like Lockheed Martin and Boeing benefiting from contracts and offset obligations, which require 30–50% of contract value to be reinvested in India’s defense industry.

France: Rafale Jets and Economic Gains

France has solidified its position as India’s second-largest arms supplier, accounting for 18% of India’s arms imports in 2016–20. The flagship deal is the $5.4 billion contract signed in 2016 for 36 Rafale jets, equipped with Meteor beyond-visual-range missiles, enhancing India’s air superiority.

Deliveries began in 2019, with all jets operational by 2022. France also supplies Scorpene-class submarines, with the first, INS Kalvari, commissioned in 2017.

France’s motivations blend strategic and economic imperatives.

The Rafale deal supports France’s defense industry, particularly Dassault Aviation, and aligns with liberal institutionalist principles of economic interdependence. France benefits from offset agreements, with 50% of the contract value reinvested in Indian firms like Reliance Defence. Strategically, France seeks to deepen ties with India as a counterweight to China, evidenced by joint exercises like Varuna and Garuda. The 2015 International Solar Alliance and annual defense dialogues since 2018 further cement this partnership.

Israel: Drones and Battlefield Testing

Israel, contributing 13% of India’s arms imports in 2016–20, is a key supplier of advanced drones and missile systems. Notable deliveries include Heron Mark 2 surveillance drones and Harop loitering munitions, used effectively in clashes along the Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan. In 2019, India employed Harop drones to target Pakistani air defenses, demonstrating their battlefield efficacy. Israel also supplies Barak 8 missile defense systems, co-developed with India’s DRDO.

Israel’s motivations combine commercial and strategic goals.

Drone exports generate revenue for companies like Israel Aerospace Industries, while India’s use of these systems in real-world conflicts provides valuable combat data, enhancing Israel’s global market position. Strategically, Israel strengthens its influence in South Asia, aligning with India against mutual threats like terrorism. The Indo-Israel Management Council facilitates joint R&D, supporting liberal institutionalist frameworks of technological cooperation. However, the “testing ground” narrative oversimplifies Israel’s intent, as commercial profits often outweigh experimental motives.

Russia: A Waning but Critical Partner

Russia remains India’s largest arms supplier, though its share has plummeted from 76% in 2009–13 to 36% in 2019–23. Key systems include the $5.43 billion S-400 air defense system deal signed in 2018, with deliveries starting in 2021, and Su-30MKI jets, which form the backbone of India’s air force. Russia also co-developed the BrahMos missile, a cornerstone of India’s arsenal.

Russia’s motivations are primarily economic, as India is its largest arms market.

The S-400 deal, signed in rubles to mitigate sanctions risks, signifies Russia’s reliance on India for revenue amid declining global exports (down 53% in 2019–23). Strategic cooperation, rooted in historical ties since the 1962 Sino-Indian War, persists through joint ventures like BrahMos Aerospace. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and subsequent sanctions have delayed deliveries, prompting India to diversify.

The “Testing Ground” Narrative: Myth or Reality?

The notion that India serves as a “testing ground” for foreign weapons assumes suppliers deliberately use India’s conflicts to test systems. While India’s use of Harop drones and Rafale jets in LoC clashes provides suppliers with combat data, this narrative overstates intent.

- Commercial Drivers: Arms sales are primarily profit-driven. Israel’s drone exports, for instance, prioritize revenue over experimental goals, with India’s $2 billion defense partnership with Armenia in 2020 reflecting similar motives.

- India’s Agency: India actively selects systems to meet specific threats, as seen in its use of Predator drones against China’s LAC incursions. India’s rigorous procurement process, though complex, ensures alignment with national priorities.

Rather than a passive laboratory, India leverages foreign technology to bridge capability gaps while building indigenous systems.

India’s Indigenous Defense Industry: A Path to Self-Reliance

India’s defense industry, 60% government-owned, is rapidly expanding, driven by the “Make in India” initiative launched in 2014. The BrahMos missile, developed by BrahMos Aerospace (a 1995 Indo-Russian joint venture), exemplifies this progress. With a range extended to 800 km in 2024 after India’s MTCR entry in 2016, BrahMos is deployed across land, sea, and air platforms. In 2022, India secured a $375 million deal to export three BrahMos coastal batteries to the Philippines, with interest from Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand.

Other indigenous systems include:

- Akash Air Defense System: Exported to Armenia in 2022 for $720 million.

- Pinaka Rocket System: Attracting interest from ASEAN and Gulf nations.

- Tejas Light Combat Aircraft: Pitched for export despite domestic challenges.

India’s defense exports reached ₹21,083 crore ($2.5 billion) in FY24, a tenfold increase from 2016–17. The government aims for $5 billion in annual exports by 2025, supported by import bans on 101 items (2020) and 108 items (2021). Private firms like Tata and Adani, contributing 90% of 2021 exports, are expanding, with Tata producing Kestrel vehicles and missile components.

Despite progress, challenges persist.

A 2022 BrahMos misfire into Pakistan and crashes of Dhruv helicopters in Ecuador (2009–15) highlight reliability issues. India’s $130 billion military modernization plan through 2027 relies on both imports and domestic production, balancing self-reliance with strategic partnerships.

Pakistan’s Arms Alliances: China, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and the Pursuit of Strategic Autonomy

Pakistan, a key player in South Asian geopolitics, has strengthened its military capabilities through strategic partnerships with China, Turkey, and Azerbaijan, countering India’s growing defense prowess and regional influence.

With a defense budget of approximately $7.8 billion in 2024 and a 43% increase in arms imports from 2019–23 (82% from China), Pakistan relies on these allies for advanced weaponry, including J-10 fighters, Bayraktar TB2 drones, and military expertise.

These alliances, shaped by shared identities, pragmatic interests, and regional rivalries, reflect both constructivist norms like Muslim solidarity and realist calculations against India and the United States.

Pakistan’s Arms Suppliers: A Strategic Triad

China: The All-Weather Friend

China, Pakistan’s largest arms supplier, accounted for 82% of Pakistan’s arms imports in 2019–23, a significant rise from 51% in 2014–18. Key systems include J-10C fighter jets equipped with PL-15 long-range missiles, JF-17 Thunder jets co-developed with Pakistan, and Wing Loong II armed drones.

In 2022, Pakistan inducted 25 J-10Cs, enhancing its air combat capabilities against India’s Rafale jets. China also supplied Type 054A/P frigates for the Pakistan Navy, with four delivered between 2021 and 2023, bolstering maritime security around the Gwadar port.

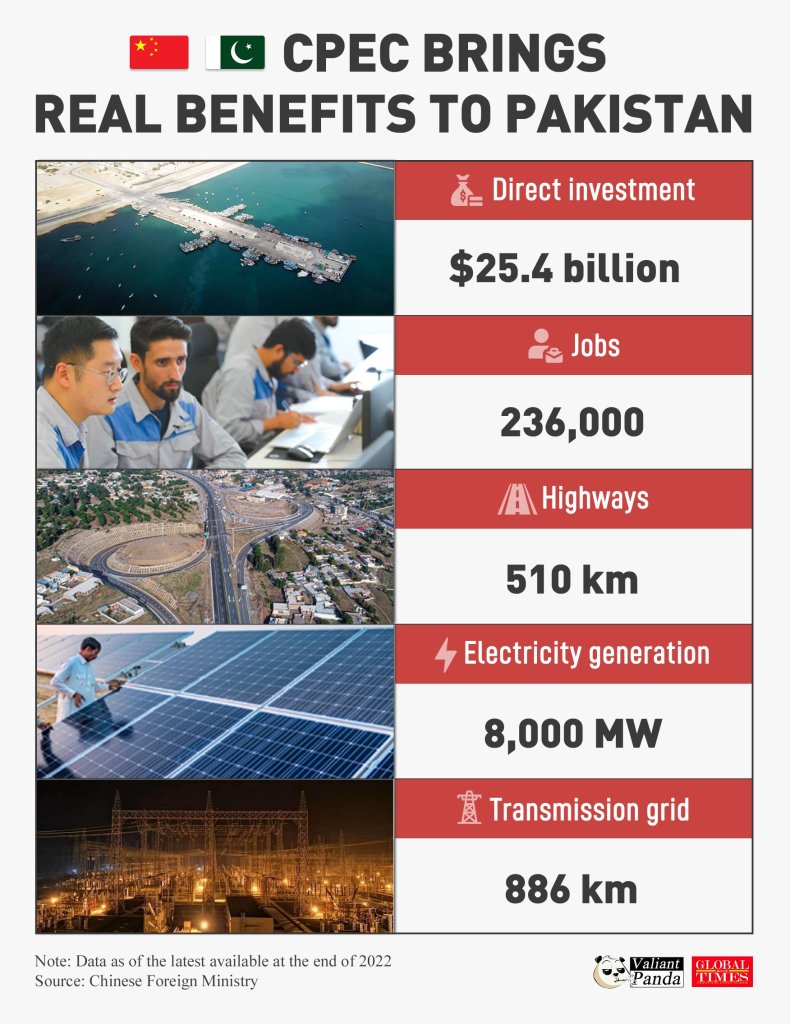

The $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship Belt and Road Initiative project launched in 2015, underscores their strategic alignment. CPEC includes infrastructure like the Gwadar port, highways, and energy projects, with China reportedly deploying weapons to protect these investments. For instance, Chinese drones and air defense systems have been spotted near CPEC sites, ensuring security against Baloch insurgents and potential Indian threats.

China’s motivations are pragmatic, driven by its rivalry with India and the United States.

Arming Pakistan balances India’s military edge, particularly along the Line of Control (LoC), where Chinese drones were used in 2020–21 clashes. Economically, arms sales and CPEC generate revenue for Chinese firms like NORINCO and CASC, with Pakistan’s $1.5 billion annual arms imports sustaining China’s defense industry. However, constructivist elements are evident in the rhetoric of an “all-weather friendship,” rooted in shared anti-India sentiments since the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

Turkey: Drones and Muslim Solidarity

Turkey has emerged as a significant arms supplier, leveraging its success in drone warfare during conflicts like Nagorno-Karabakh (2020). Pakistan has acquired Bayraktar TB2 drones, which proved effective in Azerbaijan’s victory, and the more advanced Akinci drones, with deliveries starting in 2023. In 2021, Pakistan and Turkey signed a $1.5 billion deal for 30 T129 ATAK helicopters, though delays due to U.S. engine export restrictions have shifted focus to drones. Turkey also modernized Pakistan’s Agosta-class submarines, with the first upgrade completed in 2022.

Turkey’s motivations blend constructivist and strategic elements.

The “Three Brothers” alliance with Pakistan and Azerbaijan, formalized through joint military exercises like Eternal Brotherhood in 2021, is rooted in Muslim solidarity and shared Turkic-Islamic identity. Turkey’s defense firms, such as Baykar, benefit economically, with TB2 exports generating $2 billion globally by 2023. Strategically, Turkey seeks to expand its influence in South Asia, countering India’s alignment with Western powers and Israel. Pakistan’s use of TB2 drones in LoC skirmishes provides Turkey with combat data, enhancing its global marketing of drone systems.

Azerbaijan: Military Expertise and Diplomatic Support

Azerbaijan, a newer ally, contributes military expertise and diplomatic backing rather than large-scale arms supplies. The “Three Brothers” alliance, strengthened by Azerbaijan’s 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh victory, facilitates knowledge-sharing on drone warfare and asymmetric tactics. In 2022, Pakistan and Azerbaijan signed a defense cooperation agreement, including joint training and intelligence-sharing. Azerbaijan has supplied small arms and training simulators, with a $100 million deal reported in 2023.

Azerbaijan’s motivations are primarily ideological, rooted in constructivist norms of Muslim solidarity. Its support for Pakistan’s stance on Kashmir mirrors Pakistan’s backing of Azerbaijan’s Nagorno-Karabakh claims. Diplomatically, Azerbaijan strengthens Pakistan’s position in forums like the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), where both nations advocated for Afghanistan’s reconstruction in 2021–22. Economically, Azerbaijan benefits from Pakistan’s $2 billion defense market, though its contributions are modest compared to China and Turkey.

Proxy Warfare or Arms Market Competition?

The proxy warfare hypothesis posits that global powers are using India and Pakistan to test next-generation weapons—drones, missiles, and electronic warfare systems—while boosting their arms industries.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict (2020) offers a precedent, where Turkish TB2 drones and Israeli LORA missiles proved their efficacy, enhancing export prospects. Similarly, the Russia-Ukraine war has showcased drone warfare, influencing India and Pakistan’s adoption of UAVs.

Realist scholars might argue that major powers exploit regional conflicts to gain strategic advantage, testing weapons in live combat without direct involvement. For instance, Israel’s Harop drones targeting Pakistani air defences provide valuable data on their loitering munitions, while China’s J-10 fighters face off against French Rafales, offering insights into air combat dynamics. Turkey’s TB2 drones, used by Pakistan, reinforce Ankara’s reputation as a drone superpower, attracting buyers like Ukraine and Azerbaijan.

Yet, this narrative oversimplifies the arms trade.

Commercial interests, not just geopolitical strategy, drive sales. France’s Dassault Aviation and Israel’s IAI compete for India’s lucrative market, while China’s CAIC and Turkey’s Baykar seek to expand their global footprint through Pakistan.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) notes that India and Pakistan are among the top 10 arms importers, making them attractive customers. The assumption that these powers orchestrate a proxy war ignores the demand-driven nature of arms purchases, where India and Pakistan actively seek technologies to address security dilemmas.

Critical Assumptions and Risks

The “testing ground” thesis rests on several assumptions that warrant critique:

- Intentional Testing: It assumes global powers deliberately engineer India-Pakistan clashes to test weapons. However, arms sales often precede conflicts, driven by long-term defence contracts rather than opportunistic testing. For example, India’s Rafale deal (2016) and Pakistan’s J-10 acquisition (2022) predate the 2025 escalation.

- Proxy Control: The term proxy warfare implies external powers control India and Pakistan’s actions. Both nations, however, exhibit strategic autonomy, with India pursuing global power status and Pakistan leveraging CPEC to bolster its economy. Their decisions reflect national interests, not foreign manipulation.

- Escalation Blindness: The narrative underestimates the nuclear risk. A 2019 study estimated that an India-Pakistan nuclear conflict could kill 50 million and trigger global famine. External powers, aware of this, advocate de-escalation, as seen in US, China, and Russia’s calls for restraint post-Pahalgam. The assumption that they would fuel a proxy war disregards their interest in regional stability.

From a neorealist perspective, the anarchical international system incentivizes arms races, as India and Pakistan seek to balance each other’s capabilities. External powers exacerbate this by supplying weapons, creating a security dilemma where each side’s buildup threatens the other. Liberal theorists, however, might argue that diplomatic interventions—like the US-mediated ceasefire in 2025—mitigate escalation, suggesting a preference for stability over prolonged conflict.

The Broader Implications

The influx of advanced weaponry into South Asia has transformed the India-Pakistan conflict into a technologically sophisticated battlefield, with drones and missiles redefining warfare. This aligns with postmodern warfare concepts, where information and perception—amplified by Pakistan’s information warfare tactics—shape outcomes as much as hardware.

For global powers, the stakes extend beyond arms sales. The US and China view South Asia through the lens of their great power competition, with India as a counterweight to China and Pakistan as Beijing’s strategic partner. Turkey and Azerbaijan strengthen their regional influence, while Israel counters Iran’s alignment with Pakistan. Russia, straddling both sides, maintains strategic flexibility. These dynamics reflect a multipolar world, where regional conflicts intersect with global rivalries.

However, the proxy warfare label risks oversimplifying a complex conflict. India and Pakistan’s historical animosity, fueled by Kashmir and terrorism, drives their military buildup more than external agendas. The arms race, while profitable for suppliers, heightens the risk of miscalculation, particularly given the nuclear threshold. The international community, including the UN and Gulf states, has urged dialogue, but entrenched nationalist narratives—evident in India’s Operation Sindoor and Pakistan’s Two-Nation Theory rhetoric—complicate de-escalation.

Conclusion: A Testing Ground or a Powder Keg?

While India and Pakistan’s conflict showcases advanced weaponry from global powers, the notion of a deliberate proxy warfare testing ground is only partially supported. Arms industries benefit from South Asia’s demand, and battlefield data from drones and missiles informs future designs. However, commercial imperatives and strategic alliances, rather than orchestrated testing, primarily drive arms flows. International relations theories—realism, liberalism, and constructivism—reveal the interplay of power, cooperation, and identity in shaping this dynamic.

Critically, the proxy war framing underestimates India and Pakistan’s agency and the catastrophic risks of escalation. External powers, while complicit in fueling the arms race, are not puppet masters but opportunistic players in a volatile region.

The real danger lies in the security dilemma, where each side’s pursuit of deterrence could spiral into nuclear catastrophe. As the ceasefire holds tenuously, the international community must prioritize diplomacy over profiteering, lest South Asia becomes not a testing ground, but a global tragedy.

Leave a comment