By MEI News Analysis, May 26, 2025

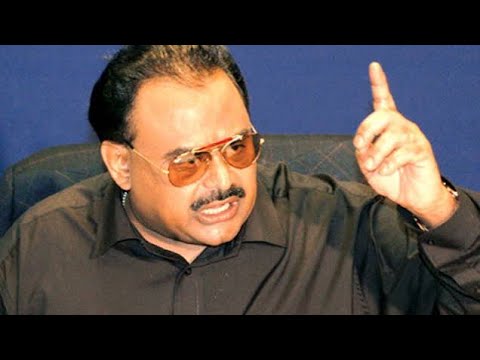

For decades, Altaf Hussain, the founder of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), has been a polarising figure in Pakistan’s political landscape. From his self-imposed exile in London, Hussain has championed the cause of the Muhajir community, a group he claims faces systemic discrimination in Pakistan. His fiery rhetoric, including a 2016 speech that led to violence in Karachi and his subsequent acquittal on terrorism charges in the UK, has kept him at the centre of controversy. Yet, despite allegations of inciting violence and a fractured party, Hussain’s influence over the Muhajirs endures, raising questions about their identity, grievances, and unwavering loyalty to Pakistan.

Who Are the Muhajirs?

The Muhajirs, meaning “migrants” in Urdu, are descendants of Urdu-speaking Muslims who migrated from India to Pakistan during the 1947 Partition. Originating from regions like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Gujarat, they settled primarily in urban Sindh, particularly Karachi, which was then Pakistan’s capital.

Their migration was driven by the promise of a homeland for Muslims, a vision they supported through the Pakistan Movement led by figures like Sir Syed Ahmed Khan.

Today, estimates of the Muhajir population vary widely due to contested census data. The 2017 Pakistani census places their numbers at around 14.7 million, though Muhajir nationalist groups claim figures as high as 22-30 million, largely concentrated in Karachi.

A 2023 Karachi University study highlights their socio-economic diversity: 9% are upper-class, 17% upper-middle, 52% middle, 13% lower-middle, and 9% lower-class.

Historically, Muhajirs dominated business and civil services due to their education and urban base, but a 2019 study by Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Center notes that Muhajir women now have the highest employment rates and incomes among Pakistan’s ethnic groups, reflecting their continued economic resilience.

A History of Marginalisation

Hussain’s rise in the 1980s was fuelled by the Muhajirs’ sense of exclusion.

Despite their early prominence in Pakistan’s bureaucracy, policies under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s government in the 1970s, such as quotas favouring rural Sindhis, sidelined Muhajirs in civil service and education. Hussain himself claims he was rejected from the Pakistan Army because of his parents’ Indian origins, an experience that shaped his political mission. The All Pakistan Muhajir Students Organisation (APMSO), founded by Hussain in 1978, evolved into the MQM in 1984, advocating for Muhajir rights in a country they helped create.

The Muhajirs’ grievances were compounded by ethnic tensions in Karachi, a melting pot of Sindhis, Pashtuns, Punjabis, and Baloch.

The 1985 death of a Muhajir student, Bushra Zaidi, sparked riots with Pashtuns, followed by the 1986 Aligarh Colony massacre, where Afghan migrants attacked Muhajir neighbourhoods. These events cemented the MQM’s narrative of victimhood, with Hussain rallying supporters against what he called “inhuman discrimination” and “economic massacre” of Muhajirs.

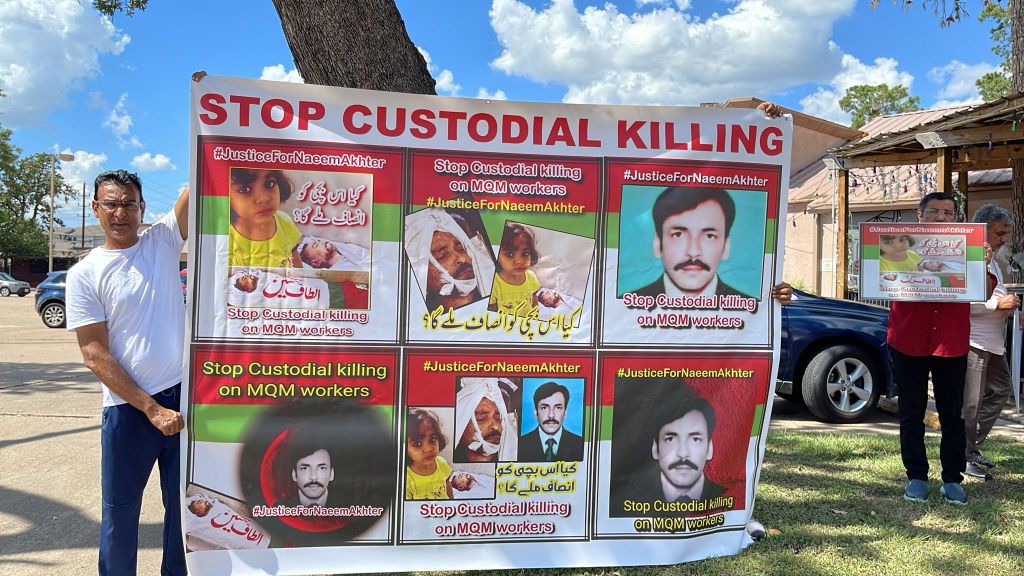

Violence and Human Rights Abuses

The MQM’s ascent was marred by violence.

From the late 1980s, the party’s militant wing, allegedly including groups like the Black Tigers, was linked to targeted killings, extortion, and political assassinations. Reports from the 1990s describe Karachi as a city where “not even a leaf would bristle without [Hussain’s] permission.”

A 2010 ResearchGate study cites MQM’s involvement in “street-gang methods” and “mafia-style” extortion, with young recruits as young as 13 wielding automatic weapons.

The 1992 Operation Clean-Up by the Pakistani military targeted the MQM, resulting in over 10,000 activist deaths between 1992 and 1999, according to some estimates. Dr Nichola Khan, a social anthropologist, testified in Hussain’s 2022 UK trial that MQM workers faced “extrajudicial killings” by Rangers, highlighting human rights abuses against the community.

Hussain’s critics, including Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), accuse him of inciting murder, notably the 2013 killing of PTI activist Zahra Shahid Hussain.

A 2016 speech, where Hussain called Pakistan a “cancer for the entire world,” led to MQM supporters attacking media houses, resulting in one death and multiple injuries. While Hussain was acquitted of terrorism charges, these incidents underscore the cycle of violence that has both victimised and implicated the Muhajir community.

Loyalty Amid Exclusion

Despite these challenges, the Muhajirs’ allegiance to Pakistan remains strong.

A 2009 Pew Research Center report found that 92% of Muhajirs identify primarily as Pakistani, second only to Punjabis. This loyalty stems from their historical role in the Pakistan Movement, which instilled a deep sense of ownership in the nation’s creation. Hussain himself has oscillated between demanding a separate “Muhajir subah” and advocating for equal rights within Pakistan, reflecting a desire to belong rather than secede.

Pakistan’s national narrative, built around Islamic unity and the sacrifices of Partition, reinforces this allegiance. The state’s portrayal of itself as a haven for Muslims, coupled with the Muhajirs’ cultural and linguistic integration through Urdu—the national language—binds them to the idea of Pakistan, even when they feel marginalised. The MQM’s shift from “Muhajir” to “Muttahida” (United) in 1997 was an attempt to broaden its appeal, aligning with this national ethos while still addressing Muhajir grievances.

The Establishment’s Narrative

The Pakistani establishment, particularly the military, has played a dual role in shaping Muhajir identity. While operations like Clean-Up and the 2016 crackdown on MQM’s Karachi headquarters, Nine Zero, targeted the party, they also deepened the Muhajirs’ sense of persecution.

Yet, the state’s narrative of a unified Pakistan, often propagated through media and education, discourages separatist sentiments. This narrative, combined with the lack of a viable political alternative, has kept Muhajirs tethered to the state, even as they rally behind Hussain’s calls for justice.

Hussain’s cult-like following, built on reverence and fear, further complicates this dynamic. His speeches, often delivered via telephone from London, evoke emotional and spiritual connections with supporters, who see him as a defender against a system that marginalises them. However, his exile and legal troubles, including a 2019 arrest by Scotland Yard for money laundering, have diminished his influence, with factions like MQM-Pakistan distancing themselves from him.

A Fractured Legacy

As Karachi’s demographics shift with an influx of Pashtuns and the rise of PTI’s multi-ethnic appeal, the MQM’s dominance has waned.

Yet, the Muhajir community’s grievances—rooted in quotas, ethnic violence, and economic exclusion—persist. Hussain’s warnings of “revived conspiracies” to incite ethnic strife, as voiced in his 2025 TikTok speech, resonate with those who still see him as their voice.

The paradox of the Muhajirs’ loyalty to Pakistan lies in their identity as nation-builders who feel betrayed by the nation they built.

While Hussain’s methods have drawn condemnation, his ability to articulate this betrayal ensures his enduring relevance.

Whether Pakistan’s establishment can address these grievances without resorting to crackdowns or divisive narratives remains an open question—one that will shape Karachi’s future and the Muhajirs’ place in it.

Leave a comment